Two out of 9 of the participants appeared to lose their sense of confidence along the journey.

Inclusive Community

Building at Sheridan College:

A Wayfinding Journey

2023-2024

Trafalgar Road Campus

The older adult (65+) population in Canada is growing as a result of increased longevity and population trends and is estimated to reach 22.7% by 2031 (Statistics Canada, 2019). As this trend is also being felt globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that accessible spaces will need to be established to provide qreater access to healthy aging opportunities (World Health Organization, 2022). "Healthy Aging in Canada:

A New Vision, A Vital investment" (2006) also states that, "older Canadians also make an important contribution to the paid economy", providing additional compelling reasons to promote accessible spaces and environments in all communities. Since post-secondary institutions are not only places of higher learning, but are also vibrant workplaces and gathering centres for people of all ages, this research project sought to better understand how individuals age 55+ of all abilities interact, access, and navigate the built environment at the Trafalgar Campus of Sheridan College in Oakville, Ontario,

Wayfinding

- Locations:

-

Location 1 is the Main Entrance

-

Location 2 is E-Wing 210

-

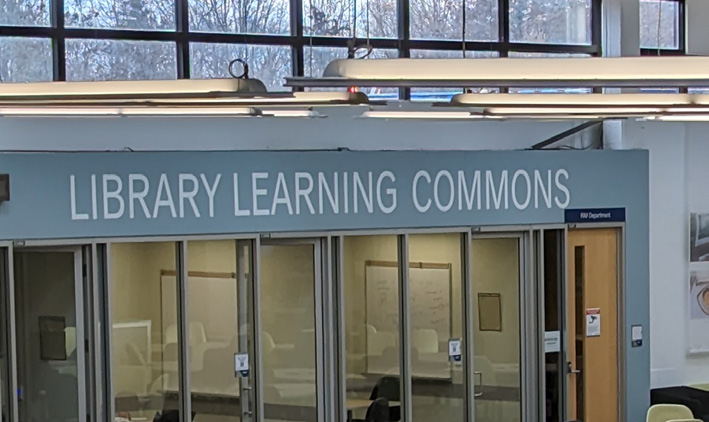

Location 3 is the LibraryLearning Services in C-Wing

- From Location 1 to Location 2 the average journey time was 9 minutes

- From Location 2 to Location 3 the average journey time was 7 minutes

The Journey

This graph shows how many of the participants were observed as to be exhibiting these feelings and traits on their journey.

The dark blue bars highlight their observed traits at the beginning of the journey to the point before they arrived at Location 2 and the light blue shows how they appeared to feel after reaching the first destination.

Eleven out of 15 of the participants expressed confusion between the Library Learning Services and Library Learning Commons signage based on observation and audio recordings.

Four participants were also confused by the IT Support Service Desk given similar naming and close proximity to the Library.

Main Entrance

"The main entrance is

poorly marked"Naming and Nomenclature

The primary point of observed confusion during the participant journey was in C-Wing on the way to the Library. Even though there is an abundance of signage in this area, with Library Learning Services and Library Learning Commons both being displayed in different places, the ultimate destination was not clear. The Information Technology Support Desk was also misperceived as being the Library, given its geographic proximity, by four participants. One participant remarked on the multiple uses of the word ‘service’ in the names, saying they thought “the service desk is the only service” so it had to be their final destination.

Top left and right: Visualization of participant’s gaze as documented by research assistant in written observation. Heat maps were generated afterwards by reenacting the participant’s gaze using an eye tracking program. Bottom left: Signage in stairwell leading to the Library. Bottom right: Signage at the service desk in the Learning Commons.

"It was a bit confusing, the

Library Learning Commons versus Services"Asking for Directions

Many of the participants were asked by passersby if they needed help looking for a destination. Nine of the fifteen participants were comfortable asking a stranger for directions; as one participant stated, “lt's more effective to just ask".

The most common location participants received direction was the Instructional Technology Support Centre. lt was also commonly mistaken for a general help desk, and although it does not have this function, the staff there were very helpful.

Signage Types

Most participants found the signage at Sheridan College Trafalgar Campus easy to read, comparing favourably with airport or hospital signs for legibility and visual accessibility. However, some noted difficulties reading signs from a distance and interpreting stair symbols without clear directional cues. A common challenge with Directory Maps was locating themselves within the map, with suggestions to add "You are here" indicators to improve navigation.

Accessibility

Ramps, particularly in specific areas were difficult for participants to find or notice, with optional ramps being used only once. One participant preferred using a ramp but missed it and took the stairs instead. Stairs posed challenges for multiple participants, who were cautious ascending or descending them, regardless of their mobility. A participant specifically found the stairs to the Library disorienting due to the lack of clear visual markers such as bright colours or depth indicators mentioning a struggle with visual depth perception.

In the passage from B wing to C wing, there are both steps and a ramp

" There isn't a ramp again

where there are stairs."

Additional Findings

In addition, some of the older adults felt that the journey was like a competition for the fasted time or aimed to get the best score. These goals were not intended for this study and as a result may have altered how they interpreted and experienced the environment at Trafalgar campus. Initially, the research team planned to document the participants on video but found it distracting and behavior-altering, as participants would directly address the camera or elaborate more on their decision-making process upon realizing they were being filmed. Consequently, the team opted against video recording to avoid influencing participant behaviour and chose instead to take photographs at less intrusive moments to document the journey.

Post-Journey User Interviews

In Conclusion

This project sought to better understand the experiences of adults 55+ as they navigated the Trafalgar Campus of Sheridan College. In general, participants were able to successfully navigate the campus, making use of a variety of legible signage options and receiving help from friendly members of the Sheridan community. On the whole, they were confident and optimistic about their journeys, though that confidence diminished slightly upon encountering certain more difficult wayfinding decision points. For example, uncertainty about going up or down a ramp or set of stairs, poor identification of elevator locations, or use of similar words on signs to describe very different destinations caused participants to make errors and increased their confusion.

These experiences highlight the need for intentional consistency among naming conventions and the optimal use of signage so that even in the face of similar-sounding destinations, navigators of the campus can find their way effectively. Furthermore, more explicit research using eye-tracking could help identify problem areas around campus that could be remedied by adjusting or modifying signage or other way-finding cues.

The research team hopes that these outcomes and the feedback from the participants will be used to inform and shape decision-making at Sheridan’s Trafalgar Campus as it relates to accessibility and wayfinding in order to optimize the experience for any campus visitor. The team will also be seeking opportunities to replicate this type of investigation at Sheridan’s other campuses. More broadly, however, this project supports the ongoing dialogues around social inclusion and an accessible society for all ages, helping to inform solutions that reduce inequalities and increase participation of all older adults in their communities.